{DISPLACEMENT} The empathic space: The moving image of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha

PENG Yuanqinghe

The tongue of the exiles was a divaricate tongue with a cruel curse full of sematic instead of meaning. Considering what their tongue always obeys by the outside language, and how the tongue experiences for an unspeakable divided space - displacement - similar to the water-drop using unreasonable way stead to the split fading river, immediately, a smooth sentence becomes a broken word in sequence by a stuttering speaker. Their fading tongue mirrored our fading memory. Meanwhile, on the other side of this cursed space, A freak show is taking place on the mirror stage. The secret of the place was the performances with their abnormal bodies. The tongue and body merge in a space marker by blanks and cuts, signifying a sense of absence.

This essay will focus on an artistic practice encircled by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, an American-Korean artist, the aesthetics of resistance to displacement with temporal, memory, and structural. Specifically, her artworks represent a map which includes a whole dislocated, dissolving, and displaced experience within the memory space. Meanwhile, I will consider a more extensive literary aspect.

The displacement evokes the linguistic recreation: the Dictée (2001)

I would like to begin by discussing the novel Dictée (2001) by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, originally published in 1982 by Tanam Press and reprinted in 1995 by First Third Woman Press. I refer to Cha's creative writing as a montage image for poetic narration because it is a two-dimensional moving image with multiple symbolic handwriting signs and ambiguous language. Cha's artistic approach, in which a navigator arises in a place between extension and compression, rupture and continuance, is wonderfully explored in this book. Cha, on the other hand, aims to create a space between memory and forgetting, inviting the audience to enter this space in order to relate the broken word to the world.

The image below symbolises the introduction of the Dictée, when ambiguity is realistically displaced. The audience is ignorant of this sign because it first appears at the outset of the book. This presents the Dictée with an anti-narrative aesthetic. The inscription translates as ‘‘Mother/I miss you/I am hungry/I want to go home.’’(Karyn,B 2006:183).This translation conveys a sense of forgetting by emphasising a theme of loss. This seems to predict a kind of recreation for the absence. As if the purity of the tongue was almost full of blackness, it left a few flickering whites, which were blurred.

(Fig 1, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Frontispiece, Dictée, 1982)

An article wrote that ‘Viewing Cha’s work as part of the history of conceptual art correlates with her stated claims about the central role of language in her work. She said: ‘The main body of my work is with language, “looking for the roots of language before it is born on the tip of the tongue’ (Best, S p121). The tongue desires purity, or we can assume that it is pure as a model of aesthetic significations.

(Dictée, p3)

Meanwhile, the purity of identity has been disappeared by the diaspora, always invisible to the space of memory. This space had never existed; however, a space was unspeakable, unreliable, and immemorial. The pure is always an end, always ending. The pain of a divaricated tongue seems like a curse. Karyn points out that the immigrant's tongue tries to speak like others in a new language but struggles, which simultaneously submits and fails to submit to the intonations of another language. Her body becomes a cipher for those who assess performance by ferreting out residues of foreignness (Karyn, B 2006:162). Moreover, In the literature aspect, for instance, Dubravka Ugiesic’s novel ‘The ministry pain’ (2008) which has a similar trauma and metaphor about the language of divided tongue. as well as supports this viewpoint from Karyn. This novel is about refugees from the former Yugoslavia and exiles in Amsterdam. At the end of this novel, the heroine's mouth keeps spewing curses:

(Dubravka Ugrešić. The Ministry of Pain, p423-428)

The heroine is forced to confront the fragmentation of their fading mother tongue.

The displacement of memory seems to be the curse of language. The Ministry of

Pain (2005) shows the context of the exile narrative, and the displacement it shows is

in the narrative aspect. But it is clear that Cha goes deeper into language. The Dictée

remarks on the displacement of ontological language. In Cha's works, displacement

becomes her aesthetic means of resistance. It involves the morphing of words and

the alteration of sentence structure; She deconstructed the signified of Dicteè by

distorting the words, by displacing the images, which resulted in a signifier of

‘DICTATION’. She rediscovered the vowels of her mother tongue between the

French and English she knew well. This is also the space she creates through

displacement.

In layer of forgetting, increasing the den-sity of mist, the opaque light fading it to absence, the

object of memory.(Dicteè, p108)

In Dicteè, Cha uses this kind of word morphing, but also points to an essentialism of displacement. In the analysis of the Dicteè, Karyn suggests that ‘Folding memory into its layers, forgetting not only increases, but also hyphenates and thus divides the ‘den-sity’ of mist while opaque light fades memory to absence’ (Karyn, B 2006:177). But In my interpretation, thus seen as paradoxically associated leads to the ‘den’ of the womb, a kind of maternal purity. The ’den’ as a womb, the ‘sity’ refers to the concentration of the memory.

The Dicteè presents a linguistic transformation of the meaning of words, and creates a magical flux of words as if they were dividing cells. Words are a representation of knowledge. When we read those deconstructed words, we still remediate our memory with those words. Generally, due to the intense pain of the trauma itself, the narrative itself is strong enough to move the audience into the story. For instance, The Ministry of Pain presents the trauma of this narrative. But the Dicteè is essentially anti-narrative, and uses an extremely innocent way of allowing empathy to happen. The particularity of Dicteè is that it deconstructs the trauma in its text. The word itself becomes a symbol of trauma, a symbol that is allowed to be recreated. Density of den, density is defined as the womb divided by memory. There are some words that have been given significance by Cha, and the audience has written them afresh.

On the other hand, Karyn suggested that’ the montage format of the poem is conspicuously informed by Cha’s studies in Paris with Metz, Bellour, and Kuntzel and a nexus of psychoanalytic, structuralist, and film theories. (B, Karyn, 2006:165). In addition to drawing inspiration from French film theory, cha's work exhibits elements of structuralist cinema, which I shall discuss in more detail below.

Following Cha's early moving image work Mouth to Mouth (1974), which presents a kind of displacement between the image as subject and the sound as text. Specifically, the screen begins with slow-moving English words, while the audience hears an unidentifiable noise. What then happened was that the mouth produced indecipherable Korean vowels, as if the snow and cold perfume were drowning one's lips slowly. It was difficult to identify the exact source of the noise; all we heard was the sound of water, or perhaps the sound of saliva being licked from her tongue. Both clear and ambiguous tones left an indelible mark on the snow. The audience sees Cha’s mouth in close-up as it makes “O” shapes on screen. Gazed deep into the snow on the screen, as if gazing into the process of some small eggs becoming an insect. The close-up and the sound overlap each other until they eventually fade into silence. The noise is overlaid with streams of water, which are constantly dissolving on the screen.

(Fig 2, Mouth to Mouth, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha,1975, 8 min, b&w, sound)

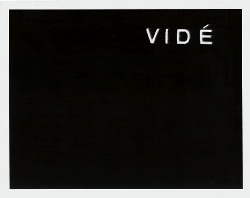

(Fig 3, Vidéoème,Theresa Hak Kyung Cha,1976, 4:42 min, b&w, sound)

The Vidéoème (1976) is a continuation of thinking similar to Mouth to Mouth(1974), it

transforms both image and sound into the text, showing a linguistic concept that

contrasts between English and French. After the word ‘empty’ appears on the

screen, the words ‘to see’ emerges above the blackness. But the sound exhibits

virtual displacement, as the English pronunciation ‘to see’ is heard a few seconds

later when the image of words ‘emptied’ appears. This montage is a displacement

between the sound/pronunciation and the text that adheres to the image.

Best suggests that ‘Vidéoème uses two of the psychic mechanisms that, according to

Freud, are more often deployed to disguise unconscious wishes or ideas:

condensation and displacement.’ (Best, S, P127). First of all, we can see that

linguistic condensation, for example, the ‘videoeme’ is formed from video+poem, this

emphasises the poetic part of linguistics and reinforces the kind of ambiguous poetry

in cha work. Meanwhile, the ‘videoeme’ is formed from video+empty as well. Such an

interpretation emphasises the condensation between the image and the text even

more, due to the image being a whole infiniti of black, the text becomes the only

visible element in the video. The text is an empty image, as if a form of

memorization. Secondly, the displacement, which shows a continuity that breaks like

a stutter. In addition to the kind of sound-image displacement recounted in the

previous, The Vidéoème (1976) also exhibits a kind of semantic displacement. Due

to the combination of French and English, the two languages are on different layers; as polyphonic music, the voice is like a moving conductor of this polyphonic music.

This performance expands the significance of the words, which are more complex

and varied, to evoke our unconscious memories.

Whereas, the ambiguity of meaning is the main reason for creating empathic space in Cha's works. The symbol, always defined by a stable subject, is related to the signified, but the signifier of a symbol is fluid. The space created by Cha’s work points to an illusion without analysing, as the illusion stems from the time when her text was created, mixed with ambiguity that blurs the relationship of signification. In this sense, the symbolic system had been deconstructed through her works, leaving only the signifier to the spectators rather than the signified.

Cha's work presents this quality as avant-garde art, with a change of sign and signification. As Peter Wollen wrote, ‘I think, very early on, to represent a critical semiotic shift, a changed concept and practice of sign and signification, which we can now see to have been the opening-up of a space, a disjunction between signifier and signified and a change of emphasis from the problem of signified and reference, the classic problem of realism, to that of signifier and signified within the sign itself.' (Wollen, P, 1975: 135). Hence, the linguistic break in Cha's work seems to be deliberate, and it gives the images a tendency towards purism and essentialism.

In addition, Cha’s moving image rejects nonlinear narrative, has an aesthetics of anti- narrative, emphasises the film's materiality and temporal aspects, and adopts an anti-narrative aesthetic. Considering the characteristics of structural film. Sitney suggests that four characteristics of the structural film are its fixed camera position, the flicker effect, loop printing, and rephotography off the screen. (Sitney, A 1974:370). Especially, the characteristics of the flicker effect, in 'Mouth to Mouth' (1974), in which the deliberate snow reflects this characteristic. The film's flicker is amplified and becomes part of the image. According to Sitney, ‘structural film approaches the conduction of meditation and evokes states of consciousness without mediation; that is, with the sole mediation of the camera.’ (Sitney, A 1974:370). The singularity of Cha's film is that this mediation switches from the camera to the physical organs, especially specific physical organs, such as the mouth. The tongue in the body, as a performative space, presents an authentic historical predicament. The body, amid a meditative state, guides the audience into an almost state of unconsciousness, and a mental subject is revealed then.

Isn't it wonderful experiencing the smell of Cha's simplest images, not just the simplest but also the most blurred? It's a scent of language that binds us and brings us back to Proust's Madeleine biscuit. In his famous novel Remembrance of Things Past, Proust describes the link between memory and smell using a madeleine biscuit from his mother's house. In 'Mouth to Mouth' (1974), when we see the shape of an 'O', we connect with our memory of the 'O'. How does the 'O' continue? a symbol, a clichéd circular line, or an ambiguous linguistic space. The mouth-shape of ‘O’ is a Madeleine biscuit, flying into the dream of the audience and evoking the area of the unconscious field with memory. As Walter Benjamin wrote in On the Concept of History, ‘The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again.’ (Benjamin, W). In this sense, the ‘O’ is the form of an image that flashes up at the instant. The past of the ‘O’, The flicker of a dot in the darkness of a night is the past of the "O," including not just light but also singing and shining. Images from the past appear in our minds, and scents change the way we remember the present. In other words, the image has the power to alter our memory much like a scent does. The image's scent suggests that we might be able to reorganise our shared memories while we wait for the ruins to subside.

I would like to refer briefly to Karyn Ball's psychoanalytic interpretation of Dictée (2001) by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha in a book of psychoanalysis and the image (2006).

I want to look briefly to Lacanian psychoanalysis to highlight the narcissism that underlies this

lack [...] According to Lacan, lack is the fruit of this internalized ideal self and, concurrently, of

the failure to fulfill the composite expectations of others, the secondary narcissistic ’I-ideal’,

that can never be completely replicated to reconvene a triumphal sense of completion and fit.

(B, karyn, 2006:173).Whereas, the ambiguity of meaning is the main reason for creating empathic space in Cha's works. The symbol, always defined by a stable subject, is related to the signified, but the signifier of a symbol is fluid. The space created by Cha’s work points to an illusion without analysing, as the illusion stems from the time when her text was created, mixed with ambiguity that blurs the relationship of signification. In this sense, the symbolic system had been deconstructed through her works, leaving only the signifier to the spectators rather than the signified.

Cha's work presents this quality as avant-garde art, with a change of sign and signification. As Peter Wollen wrote, ‘I think, very early on, to represent a critical semiotic shift, a changed concept and practice of sign and signification, which we can now see to have been the opening-up of a space, a disjunction between signifier and signified and a change of emphasis from the problem of signified and reference, the classic problem of realism, to that of signifier and signified within the sign itself.' (Wollen, P, 1975: 135). Hence, the linguistic break in Cha's work seems to be deliberate, and it gives the images a tendency towards purism and essentialism.

In addition, Cha’s moving image rejects nonlinear narrative, has an aesthetics of anti- narrative, emphasises the film's materiality and temporal aspects, and adopts an anti-narrative aesthetic. Considering the characteristics of structural film. Sitney suggests that four characteristics of the structural film are its fixed camera position, the flicker effect, loop printing, and rephotography off the screen. (Sitney, A 1974:370). Especially, the characteristics of the flicker effect, in 'Mouth to Mouth' (1974), in which the deliberate snow reflects this characteristic. The film's flicker is amplified and becomes part of the image. According to Sitney, ‘structural film approaches the conduction of meditation and evokes states of consciousness without mediation; that is, with the sole mediation of the camera.’ (Sitney, A 1974:370). The singularity of Cha's film is that this mediation switches from the camera to the physical organs, especially specific physical organs, such as the mouth. The tongue in the body, as a performative space, presents an authentic historical predicament. The body, amid a meditative state, guides the audience into an almost state of unconsciousness, and a mental subject is revealed then.

Isn't it wonderful experiencing the smell of Cha's simplest images, not just the simplest but also the most blurred? It's a scent of language that binds us and brings us back to Proust's Madeleine biscuit. In his famous novel Remembrance of Things Past, Proust describes the link between memory and smell using a madeleine biscuit from his mother's house. In 'Mouth to Mouth' (1974), when we see the shape of an 'O', we connect with our memory of the 'O'. How does the 'O' continue? a symbol, a clichéd circular line, or an ambiguous linguistic space. The mouth-shape of ‘O’ is a Madeleine biscuit, flying into the dream of the audience and evoking the area of the unconscious field with memory. As Walter Benjamin wrote in On the Concept of History, ‘The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again.’ (Benjamin, W). In this sense, the ‘O’ is the form of an image that flashes up at the instant. The past of the ‘O’, The flicker of a dot in the darkness of a night is the past of the "O," including not just light but also singing and shining. Images from the past appear in our minds, and scents change the way we remember the present. In other words, the image has the power to alter our memory much like a scent does. The image's scent suggests that we might be able to reorganise our shared memories while we wait for the ruins to subside.

The empathic space: The moving image of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and Na Mira

I would like to refer briefly to Karyn Ball's psychoanalytic interpretation of Dictée (2001) by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha in a book of psychoanalysis and the image (2006).

That is, in Lacanian theory, empathy is essentially narcissistic in relation to lack. In a sense, the empathic space itself arises out of a sense of absence, and such absence damages the subjectivity that has been disabled by identity change. Cha's personal experience shows this cruel sense of historical collective trauma and emotional displacement. Of course, it is a lack, and it is because of this lack that this protectionist, self-contradictory but both light and full empathic space was created.

At the same time, the empathic space is the attempt of the audience to perpetually remain in their hallucination. The sublimation of the object of desire, which relates to the thing (das Ding), the goal of which is ‘traversing the fantasy’(traversal of phantasy),(The Edinburgh International Encyclopaedia of Psychoanalysis, 2006). Instead, as we finally reach a fantasy that is un-traversable, the journey of analysis will come to an end. This is where the branch of methodology between phenomenology and psychoanalysis comes into view. My tendency is to think about unity in terms of the phenomenology of mind, that is, non-binary, sustaining unity between the body and the mind. As Stein wrote ‘Empathy, which we examined and sought to describe, is the experience of foreign consciousness in general, irrespective of the kind of the experiencing subject or of the subject whose consciousness is experienced.’ (Stein, E 1964:35)

However, ‘empathy’ seems to show a relationship in both object and subject. In a book On the Problem of Empathy (1964), Edith Stein wrote that:

According to Stein, the general experience of foreign consciousness is empathy. Stein attempts to systematically elucidate the phenomenon of empathy. Starting from a phenomenological approach, she tries to define the experience of the unfamiliar subject in terms of his/her experience in an ontology analysis. Stein's explanation makes me wonder if it is possible to think of one's own physical body as a coordinate. As if we can think of our affective interactions with others as a kind of displacement, the displacement of movement that takes place between the exchange of each subject. Stein clarifies that the act of ‘empathy’ is autonomy and motivation, instead of the analytical act that hides in the unconscious. One admits the objectivity of another as a subject, inversing the exterior perspective towards him/herself. Stein suggests that ‘I’ is dealing with an act that is primordial as present experience though non-primordial in content. For Stein, empathy is a way of revealing the difference between self and others. Empathy allows us to perceive subjectivity both self and other. And the act of empathy reinforces the existence of the self. Empathy, then, is an experience of radical otherness.

Hence, does this emphasise a gap between each subject that we can transform?I would like to suggest that Cha’s works had a sense of impersonality. It is this impersonality that offers the possibility of empathy, or we could say that Cha's work means to create a space for empathy. An art historian, Susan Best, identifies a sense of ‘impersonality’ in the moving images of Cha, which is included in the Visualizing Feeling: Affect and the Feminine Avant-Garde (2001). She wrote ‘impersonality is transformed from a desire to efface the subjectivity of the artist to a moving address to the audience’. That is, Cha refers to her viewer as the audience. This performance of migratory aesthetics is the performance as a transformation. Meanwhile, Best (2001) refers to Brecht's concept that the rejection of empathy is not the result of the rejection of emotions, nor does it lead to such. Best discusses empathy and emotion separately, she wrote that:

Best gives the conclusion that “Cha’s work has a mesmerising trance-like quality but does not facilitate or elicit crude empathy” (Best, S P121). However, the empathic space is a new space to place a subject and absorb emotion into space. Nor the emotional but the mental subject. Mental subjects constitute a correlation of meanings that are not arranged without logic. Logically, emotion does not construct the space but empathy can, and empathy comes from each mental subject. What we need is a non-dualistic viewpoint to provide the relationship between emotion and empathy, these two paths seem not to conflict with each other.

Stein explains the difference between emotion and empathy. Stein wrote that ‘I can not only experience a mood and myself in it, but also its penetration into me.’ (Stein, E,1964:95). Through this, we can argue that the mood represents empathy but is not solely dependent on it. The main difference is that the content of empathy comes from others, whereas the content of the preceding mood/emotion comes from the Self. Experiencing the emotions of others is an intrusion, penetration, and transference for subjectivity. Interestingly, for Stein, empathy is based on the primordial experience of another person's self-experience. In this sense, for primordial experience, I can directly read, rewrite, and narrate through myself. In the process of narration, the purity of our primordial experience is renewed and extracted. But, when we stay in the primordial experience of others, if we assume that empathy is a remediation of memory? For the content of memory arises from inner experience, which operates and returns through inner experience.

If I try to experience a kind of pain that I have not experienced before. But I can go and enjoy the pain of the other, perhaps that's a way for me to experience that kind of pain because I love others. Could we say that 'love' is the representation of empathy? Nor, ‘I’ empathise with others through my imagination, 'I’ transfer a sense of pain into it, 'I' define that pain with my own experience. It does not mean that ‘I’ have to have the same content of pain as the other person, but is that ‘I’ experience the pain as a locus of my own subjectivity. As Stein wrote that ‘We found the mental subject to be an ‘I’ in whose acts an object world is constituted and which itself creates objects by reason of its will. ‘(Stein, E 1964:87). Hence, the mental subject stays in between, which empathy evokes the medium of the mental subject. The mental subject exists independently of the medium between acts of empathy. For Stein, ‘these considerations lead us to the conclusion that the mental subject is essentially subject to rational laws and that its experiences are intelligibly related.’ (Stein, S 1964:89). Each subject has a unique perspective on the world. Mental subjects are a correlation of meanings. They are logically arranged.

The empathic space is reproduced by the moving images: Theresa Hak Kyung

Cha and Na Mira.

Considering the relationship between Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and Na Mira. An unfinished film, White Dust from Mongolia (1980-.), which was Cha's last work in her lifetime, left behind an archive of footage. Na Mira, as an artist, shares imaginative experiences with Cha. She uses her primordial experience to relate to Cha's mental subject. Her primordial experience of this 'I' for an individual who is a stranger to Cha's life, the 'I', to empathise with Cha's subject.

However, what distinguishes empathy from memory and fantasy? Since the self is where memory and fantasy originate and continue to come through self-experience. In contrast, the content of empathy originates in others, and the empathy is based on the primordial experience of the other person. As Stein wrote that ‘So now to empathy itself. Here, too, we are dealing with an act that is primordial as present experience though non-primordial in content. [...] Thus empathy is a kind of act of perceiving [eine Art erfahrender Akte] sui generis.’ (Stein, E 1964:10-12).

In this sense, we can assume that the archive of White Dust from Mongolia(1980-.) is an experience that has a primordial content, and the subjectivity of both Mira and Cha. For instance, take the act of projecting Cha’s work by Mina’s work, it is to re- project Mina’s subjectivity to Cha’s archive. That is to say, for Stein, the heterology of both Cha and Mira’s work allows it to be penetrated by the subject through the quality of simplicity. And Mira’s mental subject received Cha’s subjectivity. 'I ' use my primordial experience to empathise with Cha, i.e. The'Mira', Mira's primordial experience and re-creation through non-primordial experiences such as memories and fantasies.

Let's turn our gaze to the artistic practices associated with this. An experimental video Tesseract (test) (2020) by Na Mira. This video re-projects the train tracks scene from Cha's final unfinished film, White Dust from Mongolia (1980-.). In this work, the sound and image are not manipulated or edited (Kathy Cho, 2020-201). Rather, through project Cha’s train tracks to represent Cha’ s subject, they are subjects who project onto each other. Mira was trying to interpret that space with Cha:

The automatic writing, which is a form of automatism, the pen or pencil is then said to be guided by spirits (Chambers Dictionary of the unexplained). Automatic writing as a method to get unconscious to show the spiritual connection with each individual. Automatic writing is sometimes used as a form of divination. It connects to spiritual space. Most studies consider it to be related to the unconscious, and it also applies to the methodology of psychoanalysis. However, I argue that automatic writing is related to the phenomenon of empathy. Through this method, we seem to arrive at the goal of traversing the fantasy, but at the same time, we will stay in that endless space. This method shows an embodiment that should not be overlooked, there is the movement of our hands instead of rational thought, so that emotion takes over the space of remembering. The dream is a reflection of a memory, with the personal experience of the historical. As if Mira’s automatic writing that:

In this work, Mira mentions the surreal connection between herself, Cha, and historic memory (I prefer to change the word ‘history’ to ‘herstory’), which might be considered as a form of transcendental phenomenology. It is based on the Cha’s spiritual space. The unfinishable film creates a gap that needs to be transformed. That is, from Mira's experience, Mira accepts the experience of fantasy given to her, even if the reality of it cannot be disproved, but through the reorganisation of the soul they can reach a new place, a place constituted by a mental subject. Cha’s work as an object of empathy and desire, the object itself, transforms itself into a space, freeing itself from the influence of the other. Then, one drops into a safe water pool that would accept one’s soul to stay, like a stable eternal snowflake.

In a sense, automated writing is a process of seeing the soul of the other person as an external perception. The world in which we live is not only a world of physical bodies but also of experiencing subjects external to us, of whose experiences we know. (Stein, E 1964:10-12)). The external soul and ‘I’, are not dualistic or split; rather, our relationship with the external soul is simultaneously a component of our spiritual body. The Mental subject seems to be a den of forgetfulness. Somehow we try to experience the other mental subject through hearing, touching and feeling. Try to move my tongue towards her tongue. The tongue, as a fixation of absence, as a reflection of our mental subject, allows our subject to reject the process of objectivity.

“There exists a “Hole” in Time, a break in the linearity of Time and Space, and that empty space, the Absence, becomes the fixation, the marking that is the object of retrieval, a constant point of reference, identification, naming, the point of convergence for the narratives, the point of rupture, which gives, considers the multiplicity of narrative, multiplicity of chronology...”

( Theresa Hak Kyung Cha)

For those who have been diaspora, the cliché opinion tries to tell them the importance of searching for your roots, for the roots of your memories. However, there is another choice that you do not have to find your mother's uterus. You don't have to find out the tone of your native tongue through lost languages, the tone, which can be a mouth through water flow, light and noise. They don't have to be suffered by memories that are forgotten and can never be recalled or confirmed. In a sense, the authenticity of the memory has been dissolved with displacement of physical, regional and linguistic, and if making the connection needs to be a confirmation of the authenticity of the memory, then the pain is perpetual due to the memory can never be represented. But Cha’ works present a sense of gently wrapping in her works, which gives the possibility of space. That is, you can always be in a space that keeps displacing. In a sense, her present memories have originated in historical trauma but away from the memory. Then extricate oneself from an existential difficult position. Furthermore, the subjectivity of Cha had given place to individual spirituality. Juliana Chang's opinion is that “her use of language and images evoke a sense of impersonality, because they seem not to derive from or pertain to a knowable individual subject with whom we may readily identify” (Best, S p116).

This empathic space appears inclusive due to its unstable qualities, created with the point of ambiguity and the kind of heterogeneity signifying the object. Then ultimately pointing to a fluid and continuous creation. When Cha said that “I want to be the dream of the audience”, the dream itself immediately became an unstable spiritual space, creating endless meaning. The relationship with Cha and the audience, through the mutual coagulation and embroiling of words, symbols, Images and so on. Continuing to blur, continuing to break, continuing to flicker dimly with points of light, crying out in sleep for the dream to come again. Even divinity occasionally descends in this dream, in order to cry out once for all the eternal passions of a cruel life. That is, a mutual recognition of those subjects who are emerging from objectification, a mutual consolation as subject to subject. An enlightenment of life. Fate is utterly random. Such a space serves as a hidden thread that connects the random, where we listen to each other's breath.

Personally, I tend to trust personal memories more than historic grand narratives. I wonder how these personal narratives survived over time. Somehow, I regret that the tongue is too moist - sometimes the tongue cannot understand the other's intentions. When the tongue impresses a gap in which cannot be translated, perhaps it was showing how the refugee is being pained by these melancholy ballads. The metaphor of stuttering continually. Our tongue is a second tongue. The refugee uses everything in the second to transcend the tongue - the curse of the second song, the training, all the words become a curse chain, a single dance, the tongues roiling the blood of the body. We read poetry with a second tongue, we live for the second tongue, we use a second world. We buy a second bar of soap, a second day of discounted food, a second council tax, we see the second sky and use the sky twice, we listen to a second bird tweet. A second time to learn numbers and colours, a second time to combine Latin and Greek into Arabic. Only the second bird with wings so wide that we insist on seeing the sky behind the wing. For this reason, we will be going to end with poems — Refugee — leaves caught in your throat?

The bird, ah, was only bird.

Somehow, I would like to use this image to illustrate the scents of the image that Cha left behind. Sitting alone, without any extra movement, her inner world is projected into the cave. Her tongue left this deconstructed mouth in this abstract image.

Reference

Reference

Kyung, C.T.H. (2001) [1982]. Dictee. Berkeley : University of California Press.

Ugiesic, D. Heim, H,M. The ministry pain(2005). Saqi Books

Proust, M. Remembrance of Things Past. 2022. London: Penguin Classics.

Ball, K. (2006) ‘Diaspora without resistance? Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee and the law of genre’, Psychoanalysis and the Image, pp. 161–193.

Norma Alarcón, Elaine H. Kim, Hyun Yi Kang, Lisa Lowe, Shelley Sunn Wong. (1994).Writing self writing nation : a collection of essays on dictée by theresa hak kyung cha.Third Woman Press.

Best, S (2011) ‘The dream of the audience: The moving images of Theresa Hak Kyung

Cha’ (2011) Visualizing Feeling [Preprint]

Best, S (2011), Visualizing Feeling : Affect and the Feminine Avant-Garde, I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited, London. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. [1 February 2024].

Durrant, S. and Lord, C.M. (2007) Essays in migratory aesthetics cultural practices between migration and art-making. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Peter Wollen, ‘The Two Avant-Gardes’, 1975, Art and the Moving Image: A Critical Reader, Afterall Books/MIT Press

Sitney, P.A. (1979) Visionary film: The American avant-garde. Oxford: Univ. Press. Bammer, A. (1999) Displacements: Cultural identities in question. Boulder, CO:

NetLibrary, Inc.

Kyung, C.T.H. (2001) Der Traum des publikums = the dream of the audience. Vienna: Generali Foundation.

Hartman, S. (2023) ‘Venus in Two acts’, Unequal Sisters, pp. 27–37.

Benjamin, W. Walter Benjamin on the concept of history/ theses on the philosophy of history. Available at: https://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/CONCEPT2.html [Accessed: 03 February 2024].

Mouth to Mouth (1975) Ubuweb Film & Video: Theresa Hak Kyung Cha - mouth to Mouth (1975). Available at: https://ubu.com/film/cha_mouth.html [Accessed: 01 February 2024]

Vidéoème (1976) Ubuweb Film & Video: Theresa Hak Kyung Cha - Vidéoème (1976). Available at: https://ubu.com/film/cha_videome.html [Accessed: 01 February 2024]

Artist (2022) The Dream of the Audience. Available at: https://theresahakkyungcha.com/artist/ [Accessed: 01 February 2024].

A ble W AIL (1975) Online Archive of California. Available at: https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/tf1g50012k/?brand=oac4 [Accessed: 01 February 2024]

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s emotive multimedia work is ... - artsy. Available at: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-theresa-hak-kyung-chas-emotive- multimedia-work-influencing-new-generation-artists [Accessed: 01 February 2024]

Best, S (2011) ‘The dream of the audience: The moving images of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’ (2011) Visualizing Feeling [Preprint]

Best, S (2011), Visualizing Feeling : Affect and the Feminine Avant-Garde, I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited, London. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. [1 February 2024].

Kathy Cho, 2020–2021 Curatorial Fellow (2021) Na mira: ‘passages paysages passengers’, The Kitchen OnScreen. Available at: https://onscreen.thekitchen.org/media/na-mira [Accessed: 01 February 2024]

Kathy Cho, 2020–2021 Curatorial Fellow (2021) Na mira: ‘passages paysages passengers’, The Kitchen OnScreen. Available at: https://onscreen.thekitchen.org/media/na-mira [Accessed: 01 February 2024]

Artist (2022) The Dream of the Audience. Available at: https://theresahakkyungcha.com/artist/ [Accessed: 01 February 2024].

Mira, N.Na Mira / Mira / Tesseract (Test).Available at: https://www.na- mira.com/mira/tesseract-test/ [Accessed: 01 February 2024]

Tes Heures (2022) Fulcrum Arts. Available at: https://www.fulcrumarts.org/sequencing/tes-heures/ [Accessed: 01 February 2024]

Sauvignat, F. (2006). Traversal of phantasy. In R. Skelton, The Edinburgh international encyclopedia of psychoanalysis. [Online]. Edinburg: Edinburgh University Press. Available from: https://arts.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fsearch.credoreference.com%2Fco ntent%2Fentry%2Fedinburghpsychoa%2Ftraversal_of_phantasy%2F0%3FinstitutionId% 3D105 [Accessed 1 February 2024].

automatic writing. (2007). In U. McGovern (Ed.), Chambers Dictionary of the unexplained. [Online]. London: Chambers Harrap. Available from: https://arts.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fsearch.credoreference.com%2Fco ntent%2Fentry%2Fchambun%2Fautomatic_writing%2F0%3FinstitutionId%3D105 [Accessed 30 January 2024].

Fig 1, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Frontispiece, Dictée, 1982) At: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Theresa-Hak-Kyung-Cha-Frontispiece-Dictee- 1982_fig6_38105221 [Accessed: 01 February 2024]

Fig 2 UbaWeb (1975) Mouth to Mouth, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha,1975, 8 min, b&w, sound [Film still] At: https://ubu.com/film/cha_videome.html [Accessed: 01 February 2024]

Fig 3 UbaWeb (1976) Vidéoème,Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, 4:42 min, b&w, sound [Film still] At: https://ubu.com/film/cha_videome.html [Accessed: 01 February 2024]

Fig 4, Na Mira, Tesseract(test), Infrared HD video, sound 6:06, 2021 [film still] At: https://www.na-mira.com/mira/tesseract-test/ [Accessed: 01 February 2024]